|

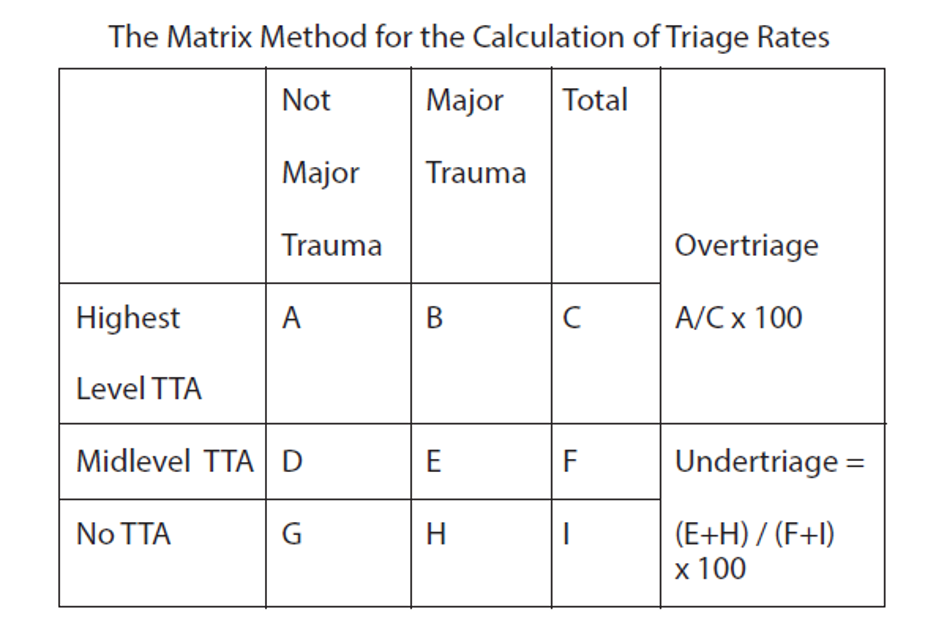

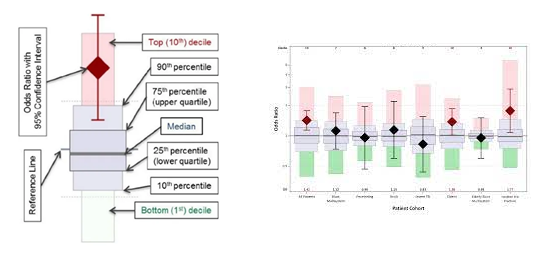

Data cleaning is the process of detecting and correcting inaccurate data from your patient records. It is the overall process that should be used to ensure the data is correct, consistent, and usable. Data cleaning starts with understanding your data, where it comes from, and what it says. The trauma registry should have a consistent data cleaning process which marks the “closing” of a month. There are many different benefits to having a solid data cleaning process for your trauma program. First, this process removes major errors and inconsistencies in your data. These inconsistencies will cause you to be high (or potentially low) outliers in your benchmarking reports. Second, ensuring a data cleaning process for monthly closure will make everyone on your team more efficient. The errors identified through data validation and data cleaning will increase the working knowledge and the interrater reliability of your trauma registrars. Third, as the interrater reliability increases, and data errors decrease, the reliability of your internal and external reports increases. This will give a new level of confidence to the trauma team as they review your benchmarking reports, and evaluate their care provided. There are basically five steps in data cleaning. 1. Monitor for errors. Keep a record of trends in either data element errors, misunderstandings, or abstractor specific errors. Observing the trends will allow you to focus your attention to these specific errors in the upcoming months, until these errors are no longer problematic. Just like with any performance improvement project, remember “Loop Closure”! Circle back in three to six months and ensure the problem has not popped back up. 2. Standardize your process. This is one of the biggest areas a trauma registrar needs to work. Each institutional trauma registry should have a data dictionary similar to the National Trauma Data Standards (NTDS) Data Dictionary. The NTDS fields will of course have the exact same definitions, but the additional information will detail exactly where in your electronic medical record (EMR) the data is found. Listing the primary and secondary data sources is key. Non-NTDS data elements will likewise need a clear definition, common null values, and the same primary and secondary EMR locations. In summary, your institutional data dictionary should be an exact road map for anyone abstracting charts. It should demonstrate the level of detail that would ensure all abstractors are abstracting data in the exact same way. 3. Validate data accuracy. We could write a book on this topic. There are so many ways that data validation occurs. First there is the International Trauma Data Exchange (ITDX) validation that is built into each trauma registry software package. This type of data validation is strictly looking for schematic errors. These are things like correct field choices (characters or numbers) correct upper and lower data element limits (such as systolic blood pressure) and that the correct rules for the data element have been followed. Typically, this will check to ensure the appropriate usage of common null values for the data element. It also contains cross reference rules where two pieces of interdependent data match, such as admission date and time occurring after the injury date and time. These schematic errors are also known as syntactic errors. These are errors in the acceptable “structure” of the trauma registry. In other words, it looks at what you put in to ensure it follows the rules without considering what it means. The ITDX thus will give you Level 1-4 errors. Level 1 and 2’s will keep your entire data submission file from being excepted, whereas Level 3 and 4’s are more warning errors for you to verify. Next, you need to look at the actual validity of the data that you entered. This is the portion of data validation that requires you to “re-abstract” key elements in the trauma registry to ensure your data is correct. See our archived article: “Data Point Inter-rater Reliability for Targeted Trauma Registrar Education Leads to Pristine Data” for more detailed information on specific data fields that should be validated. In this type of validation, we would re-abstract the initial vital signs. A systolic blood pressure of 180 was entered. Schematic validation would find this as a valid entry as it is above the lower limits and below the upper limits of the acceptable systolic blood pressure range. However, schematic validation does not know if the actual systolic blood pressure was 80, 108 or 180. Thus, direct re-abstraction must occur. 4. Analyze your data. What does your data say about your trauma department and the care you provide? This is such a loaded question. How you answer it, depends on what your data demonstrates. For example, does your W Score match your perception of your care? If you feel that you deliver excellent care, and that you have a great trauma program, yet your W Score is a negative number, you have contraindicated results. Cleaning your data and having a set monthly closure routine will ensure that your data is as accurate, relevant, and usable. 5. Communicate with your team. Share the new standardized cleaning process you have developed with your entire team. This promotes the adaptation of the process for everyone, as well as increases their confidence in the data. Remember that this data is used for your internal performance improvement program, injury prevention, and medical research. Externally, it is used on a state level for trauma system development, and nationally for injury surveillance and research. Most importantly your data is used for your benchmarking reports. As you begin to look at a monthly closure process here are some items to evaluate to see where your starting point is really at. Once you have that starting point documented, then move into the mind set of continuous site verification preparation. Below are some examples of monthly data cleaning reports, or specific trauma verification preparation reports. Both are equally as important to the overall success of the trauma registry and the data that it produces. 1. How many records do you have for the month that have a missing mechanism of injury (MOI), revised trauma score (RTS), injury severity score (ISS) or probability of survival (PoS). These are pivotal data elements that will impact your M, Z and W Scores. These are major benchmarking tools. For example, if 10% of your charts are missing an ISS, then this 10% will not be included in reports such as the W Score for unexpected outcomes per 100 patients. This “forgotten” population can adversely affect the W Score, and produce unreliable results. 2. Trauma activations without trauma attending presence documented. This is a big element for the trauma center and part of the pre-review questionnaire (PRQ) that you submit prior to your site verification visit. Keeping a handle on this monthly ensures no surprises when you complete the PRQ for submission. 3. Over and under triage is also an important monitoring tool for trauma centers. This should be reviewed monthly. Figure 1 below is found in the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Resources for the Optimal Care of the Injured manual on page 121. “Major trauma is defined as “major injury requiring the resources of the highest level of activation determined by the local center, often by data readily available in the trauma registry.”[i] Therefore, if your patients have been over or under coded, your ISS will not be correct, and the over / under triage rates will be falsely affected. Figure 1 4. Non-Surgical Service admissions is another category to monitor monthly. As part of the PRQ, facilities who have a greater than 10 percent admission rate to a non-surgical service for trauma patients, must have a dedicated performance improvement plan in place. Centers with this higher admission rate must assess the following criteria related to those admissions. a. Number with a trauma consultation b. Number with other surgical service consultation c. Number with mechanism of injury (MOI) equal to same -height falls d. Number with MOI equal to drowning poisoning, or hanging e. Number with ISS 9 or lower (and who do not meet the criteria in c or d)[i] 5. The next item is the acute transfers out of your facility. It is important to monitor this number as each case is subject to an individual case review. The review will determine the rational for the transfer, appropriateness of care and any opportunities for improvement. To close the loop of this patient population, follow up information should be obtained from the acute care hospital and be included in the case review. Acute transfers as a monthly report ensures timely case reviews as well as requests for the follow up information. 6. Data correlation reports are also important to identify any incomplete, or inaccurate data elements in the trauma registry. These reports are comparing two different pieces of seemingly unrelated data to the accuracy of the end results. For example, a report in which you review all patients with an emergency department disposition of floor, and the ICU length of stay of 1 day or more. There are situations in which this does occur, but you need to ensure you know that situation and it is documented properly in the trauma registry. In this example, the possibilities are; a) the ED disposition was incorrect, b) the ICU length of stay is incorrect, c) the patient had a routine post op ICU stay, or d) the patient had an unexpected upgrade to the ICU. If d is the answer, then you need to ensure that this is documented in your hospital events area. 7. As TQIP centers review their benchmarking reports, it is extremely important to understand where you fall on the box plot. Figure 2 below demonstrates an explanation of the box plot. The diamond is the odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval. The deciles are noted as well as the median. Figure 2 You need to review each patient cohort and see how your facility “stacks up”. Identify any issues and then this becomes the next monthly report. For example, if you are a high outlier for pulmonary embolus (PE) then each month you will look at each PE entered into the trauma registry and verify the data for accuracy. While this may seem redundant, there are several parts to the PE definition that some trauma registrars misunderstand. In the additional information section of the NTDS Data Dictionary, it states that subsegmental PEs are excluded. Additionally, PEs identified on initial scans in the ED are also excluded. The additional information states, the PE must have occurred during the patient’s initial stay at your hospital, therefore, if the PE was present basically on arrival, it occurred prior to reaching your hospital.

A deep dive into your hospital events, and validation of each can illuminate definition misunderstandings, physician documentation needs, or additional clarification for the ACS TQIP team. As you think more critically about your trauma registry data, be open to data cleaning. Just like with any home, it needs to be cleaned. This process of identifying incomplete, incorrect, inaccurate, or irrelevant data and replacing, modifying, or deleting it can turn your trauma registry into a solid cornerstone of your trauma program. Afterall that is what the trauma registry is designed for. It is the disease-specific data collection that is a vital and integral part of the trauma program. Don’t let your trauma registry become a data graveyard! It is a giant repository of limitless, useful data, if it is accurate, valid, and clean data! [i] Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured patient, Chapter 16, page 121 [i] Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient, Chapter 16, page 120 Comments are closed.

|

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

Comprehensive Trauma Program

CONTACT |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed